Google Translate – choosing between the right and the easy

Talk given at the Thomson Society, Harrodian School, January 22 2019

“To possess another language, Charlemagne tells us, is to possess another soul.“

John Le Carré

I/ What is Google Translate?

Let’s just imagine you are in Moscow. You are keen on a Russian boy you have met a week or so ago and things are going great. One day, on Tverskaya Street you heed the urge to call him “sweetheart”, or maybe just “darling”. So what do you do, if you are a 20-30-something – or maybe even older – British girl or boy – with a smartphone?

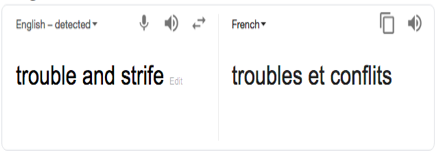

You happily use one of the options offered generously and instantly by Google. What do you get?

So far, so good. Even if he suddenly seems off-kilter and starts fearfully looking around himself, your Russian “beau” is further charmed and about to give you the kiss you have been dreaming about. But something else happens. And if you think that you’d be living a romance instead of a police thriller… think again. Imagine now that past you goes a big, close-shaved youngster with a t-shirt carrying a Putin print in front, maybe even adorned with the word РОССИЯ in old Slavonic script. When he hears the Russian word “голубчик”, what does he see?

From that Russian dictionary some things can be deduced.

Please note the italic “ironic”. This little clarification adds an important cultural dimension for the Russian – and most eastern-European societies of today.

This is what dictionaries – including online ones – give you. Context.

As the dictionary pointed out, the first and base meaning of the Russian word голуб is “pigeon” or “dove”. A derivative, “голубой” is an adjective meaning blue, sky/dove blue. The diminutive “голубчик” is used as the address ‘sweetie” or “darling” (imagine the Craig Revill-Horwood one) to a man.

In 2014 we, the UK, legalized gay marriage. To us there is nothing damning about this picture or its connotations, our open and tolerant society accepts diversity.

“Голубчики” in Russian are called, for obvious reasons, homosexual men.

In Putin’s Russia they are people not just outlawed, but openly despised, ridiculed and fiercely attacked on the streets.

How did Google Translate get you in such trouble? Let’s start from the definition. (Wikipedia)

Therefore: Google Translate does not translate.

It says so itself, in its own definition. It is:

- a statistical machine translation service. It uses all transcripts from the United Nations and our dear European Union daily deliberations to gather its base data. I cannot imagine anything duller personally. So, as in statistics, it uses a basic algorithm to find the correct word. As of 2016, Google proudly says that, based on that calculation, it can translate not just the odd word, but whole phrases, sentences, paragraphs and full texts. (In my humble 12-year teaching experience, our students were able to use it like that much before 2016).

- From any other language in the world, it must translate first into English and then on to the target language. Example: if you need to translate anything from Spanish into Italian online (everyone knows how close Spanish and Italian are), Google will offer you a third-line product, passing through English.

So –

It is a matching device for words.

It is a sophisticated word search.

It works thanks to mathematical functions and probabilities, not with language.

So you are playing Russian roulette by expecting this device to find the one white ball in a bucket of hundreds of black balls.

Even Google’s Wikipedia admits on its website that “it has been criticised and ridiculed for its inaccuracy”, but does not elaborate how the predictive algorithm would integrate cultural knowledge and the rest.

But let’s be reasonable.

It would be criminal to waste time with heavy phrase books and dictionaries if Google Translate can quickly provide a word to communicate that somebody’s life is in danger, if you are lost or helpless with a giant problem in a foreign country. Even if what you say in an emergency or distress is inaccurate, it wouldn’t matter: people usually want to help and will do their best to understand you.

Common sense tells us that Google is good to find the approximation of a word:

- For technical and urgent tasks

- For simple needs and communications

- For isolated, literal identification of words

- For directions and orientation

- For instant, immediate help

For a real conversation, for human communications, i.e. for life and truth issues, there is the power of language and (real) translation.

I guess you have been expecting the first advent of a Google Translate joke. Well here it is.

Generally, the English use this expression to mean “oh dear, I’ve done something silly” etc. But the joke is on anyone who tries to translate “oops a daisy” with the help of Google Translate.

It means nothing in French. It loses its English meaning.

I guess this might end up being the case if we translate it in Urdu, Mandarin or Spanish.

Let me use “голубчик” one more time.

One other dimension of the word comes from Russian history. Some older Russian citizens – those in their 70s for example -may shiver at the mention of the “голубчики”. For them, these were the members of the NKVD, Stalin’s secret police who wore dove-blue (or sky-blue) caps.

We, language teachers, are often confronted with the often following reaction:

“How does this concern me? This expression is too difficult, that word is too dangerous. I am already an English speaker, I am not going to start a difficult language learning, I’ll still rely on Google for the odd exchange abroad. The locals will see me brandishing my phone or my iPad and will know straight away that, if I’ve made a mess of a word, it is Google’s fault, not mine. I don’t need to talk to the locals about the meaning of life, do I?

I am not a linguist; I am not even interested in languages. All I care about is to survive abroad. Is that a sin?”

Well, there are two points to that.

First.

Even if we try consciously hard, our communications with other cultures are never reduced to, roughly “what can I buy from you/what can you buy from me”. (OR are they?)

An old leitmotif from my linguistics professors sounds roughly like that: “The moment we start simplifying or neglecting other languages, we begin to weaken our own.”

As much as we, humans, might want to choose who to live with and who to dislike, languages are not picky and choosy. They evolve through connecting with other languages, any languages, often those in close proximity. We would be condemning English – we already see the signs – to a slowburn out if we consider other languages an unnecessary knowledge.

Second.

Where do we leave our natural curiosity for different worlds, different ways of thinking, different concepts and myths? Why are we so little interested in the rituals, the beliefs and the fears of others? Where is the interest in THE OTHER? An integral part of these traditions and folklore is language.

Generally speaking, if we reduce translation to simple word matching for easy as well as for difficult linguistic tasks, we lose a significant layer of the depth of our hundreds of languages.

Because now Google’s ambitions are many. Here comes the so helpful Wiki Again.

“Functions

Google Translate can translate multiple forms of text and media, which includes text, speech, images, and videos. Specifically, its functions include:

Written Words Translation

- A function that translates written words or text to a foreign language.[6] REALLY?

Website Translation

- A function that translates a whole webpage to selected languages[7] IS THIS A JOKE?

Document Translation

- A function that translates a document uploaded by the users to selected languages. The documents should be in the form of: .doc, .docx, .odf, .pdf, .ppt, .pptx, .ps, .rtf, .txt, .xls, .xlsx.[7] I GUESS, INSTANTLY. OF COURSE.

Speech Translation

- A function that instantly translates spoken language into the selected foreign language.[8] (NOW YOU’RE TALKING. OR KIDDING.)

Mobile App Translation

- In 2018, Google Translate has introduced its new feature called “Tap to Translate,” which made instant translation accessible inside any apps without exiting or switching it.[9]WOW!

Image Translation

- A function that identifies text in a picture taken by the users and translates text on the screen instantly.[10] I GUESS IT WOULD BE FINE TO TRANSLATE IN MANDARIN A PICTURE OF A TART IN THE SENTENCE “You’re a …”

Handwritten Translation

- A function that translates language that are hand written on the phone screen or drew on a virtual keyboard without the support of keyboard.[11]

For most of its features, Google Translate provides the pronunciation, dictionary, and listen to translation. Additionally, Google Translate has introduced its own Translate app, so translation is available with mobile phone in offline mode.[9]” END OF QUOTE

As I mentioned before however, looking for the white ball in a pile of black balls is not translation. It is a game of sorts, but not a serious translation work.

It is interesting to me as a linguist why the Google executives had turned to UN and EU boring texts in search for a database. And if Google is using diplomatic language? Do diplomats use Google Translate?

The answer is a resounding “no”.

Foreign ministries around the world invest millions in language training their staff who study the culture, history and traditions of other countries in order to negotiate and avert war for example. Their official documents on the other hand use the administrative, unnatural language of institutions, but funnily enough, those tons of paperwork are much easier to access by Google’s database.

How do we expect Google to go into specific, emotive or thematic context using a system of signs as ancient as the human race – language?

II/ What is translation?

The study of language was a sister to philosophy since ancient times. Socrates and Demosthenes were fully aware of the power of language; Aristotle’s Poetics was the foundation of my university degree in Philology.

Linguistics as a science was comprehensively defined by a Swiss professor – linguist and semiotician – Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913).

Saussure developed his theory about the nature of the sign – semiotics – and the arbitrary nature of the signifier at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, during his research and lecture posts in Berlin, Geneva, Leipzig.

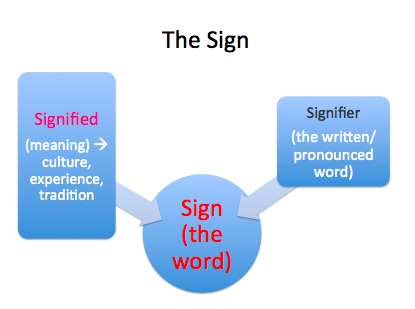

The foundation of semiotics – the science of our languages as a collection of signs – lies in the difference of these two terms: the signified and the signifier. These are the two components of the sign. For simplicity, let’s understand that sign is a synonym to word.

So each word has two components: the signified, i.e. the meaning, and the signifier: the actual uttering of sounds/phonemes combined in such a way that we give a physical name to the non-physical meaning.

Let’s translate this into a real example:

Saussure’s theory that the nature of the signifier is arbitrary is well known. For example, some of our indo-European ancestors decided to name the table “table” just like that, by chance, possibly as an onomatopoeia describing the sound of something hitting the table, or something else in that sequence of phonemes that reminded him of the object “table”. However, the image in our heads, the non-physical concept of a table is different for every single one of us. If we all had a thought bubble appear over our heads right now, I am sure that some of us will be seeing anything from our school desks to, who knows, Louis XV side tables with gold leaf plated sides.

The so called “extended semantic field” of the word “table” can include derivative verbs, for example “to table a motion” or a mythical symbol “negotiations at a round table”, and many more metaphors, similes, allegories in all Indo-European languages.

Why not now draw a comparison with the term we saw at the beginning of the talk: голубчик. As a British tourist holding on to your smartphone for dear life, using that term will mean one thing. To the Russian girl or boy you may address it, it may quite possibly mean another.

I am fully aware that this is far too simple an example.

The more complex ones are immensely more complex. Add national cultural memory, history, mythology and religion, economy and business… – all elements of the socio-anthropological conditioning of the human language. Mix with complex grammar and idiom.

Thus we arrive at the recipe – or definition – for translation.

Saussure’s theory has given birth to a few very powerful currents in linguistics and in literary criticism, namely structuralism and deconstructivism. His followers include people like Umberto Echo, Roland Barthes, Jacques Dérida and Noam Chomsky.

How do these currents affect translation?

Despite the (generally accepted) simplistic perception of grammar as maths, grammar is not just a compilation of rules and formulae. It reflects, in its very core – the Moods (Indicative, Imperative, Conditional and Subjunctive) – the irrational nature of humanity and of its tool – language.

If we accept that in the transfer of word for word in most cases Google Translate is likely to be harmless, in longer texts the compounded dislocation between signified and signifier becomes tragic. Have you tried to read your Chinese horoscope? The website – if it comes from China – usually looks written in English, but the text is fantastically unreadable.

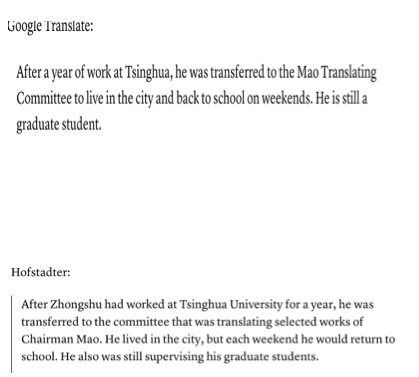

Here is an example of Google versus professional translation from mandarin used in an article in The Atlantic by Douglas Hofstadter (January 30th 2018):

Can we afford to put up with such distortion of the narrative? Do we believe that such attack on language is worth accepting because “it saves us hours of effort”? What is the right thing to do, not the “easy” thing to do?

Here is an illustration of the complex structure of languages, once we come out of the simple zone of the word.

Languages as scientific concepts are multifaceted creations of centuries of humanity. Saussure’s theory explained and tried to put into the context of global human history a classification of languages by cultural groups.

III/ What is the job of a translator?

Jean-François Ménard, translator in French of the “Harry Potter” series

So, faced with so many layers of knowledge, what is the job of a translator?

Jean-François Ménard spent 126 hours per week translating JK Rowling’s epic novels. He used to start from the first chapter and follow with the last, then second chapter, followed by the penultimate, in order to keep his mind awake to any complacency regarding the vast layers of meaning and research with which Rowling had infused her books. Here are some of his ingenious translations:

Poudlalrd = Hogwarts (bacon lice)

Poufsouffle = Hufflepuff

Les Mangemorts = the Deatheaters

Snape (Old English) = Rogue (Old French)

Some inferred meanings like those in Diagon Alley and the Knight Bus he could not translate with and equivalent “pun” in French. So he chose to make his own – a creative allowance that any good author would respect and enjoy from a good translator who can match the spirit of the novel: His own joke creations to replace the jokes he could not translate:

Le Choixpeau = the Sorting Hat

Ratconfortant = rat tonic

Ménard was Rowling’s favourite translator as well as Roald Dall’s.

IV/ How translation saves the world

Books are translated from one language to another. Books are also translated from an older version to a newer version.

That sort of translation is revolutionary.

Let’s look at the Bible.

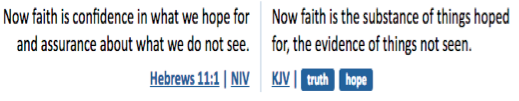

The King James’ translation from 1611 revolutionalised British history and education. This translation from Latin was so brilliant, all these 500 years ago, that to this day we use expressions from its pages like “you are the salt of the earth”, “see the writing on the wall”, “broken-hearted”, you name it!

This translation was used until not that long ago, when the Church of England realized that too many people felt disconnected with its values and its language. So it ordered a new translation that reflected the language and imagery of the modern times.

The Passive voice of the excerpt from King James’ Bible is heavy and outdated. The simplicity of the New International Version does not lose the meaning, but brings the scripture closer to the reader.

People “translate” the Bible – or any other book for that matter – according to their modernity, to the requirements of their present, in order to communicate correctly the meaning(s) to the culture of today.

Machines have no temporal or emotional understanding so far; they cannot yet transmit linguistic ideas beyond the literal.

They only replicate human language, although they can learn and they are learning fast, from us. But, seemingly, not fast enough.

This will be exemplified by this following experiment:

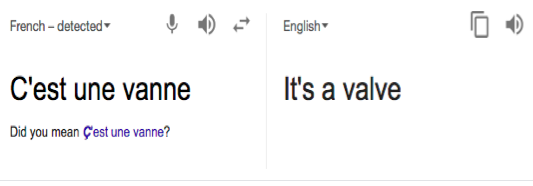

Translating slang. For the older and wise ones amongst us, this is what happens to the almost forgotten cockney slang.

(What ‘appened to the wife?)

Let’s try Google on current French slang.

(No, it’s a “joke”!)

Ohlala. What about Englsih teenagers? The greatest fans of Google Translate. Well, they’ve managed to build a language that even their parents find hard to keep up with. What do you think “that’s peak!” means? What about, “Oh, she’s butters”?

So if a French teenager is faced with one of those terms and runs to Google Translate for dear life, what will he/she get?

This is a good illustration that the Internet could be a very good place to find the proper meaning of a word – as long as you don’t go to Google Translate. The Urban Dictionary, Collins, Larousse online etc, are by far your better options.

Trouble is, Google can’t keep up with not just current slang; it can’t keep up even with older familiar language, because it is removed from human society.

Google translate does not sit with our teenagers at the dinner table and does not ask the teens to tell him what this and that means.

Hence the following experiment.

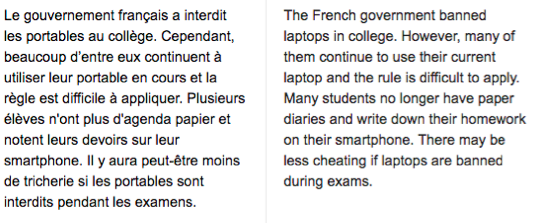

I asked Google to translate the GCSE mock exam translation 2017 from French into English.

Google has not yet captured the natural shortening evolution in French of the word “un telephone portable” – everyone shortens it to “portable”. Instead it translates it into “laptop”. According to Google, the students used to write homework (not to note it down) in their paper diaries (paper planners) but now they write homework (!) on their smartphones.

Students use Google and probably will nevertheless, even if it fails them every time. It is easy.

Adults do too, even renowned companies do it.

A very good friend of mine manages a team of subtitling translators for a company serving HBO among others. An ever-shrinking team of translators. Instead of translating frame by frame as before, now they are required to correct the already machine prepared text of films, to add emotion, context, cultural value. Machines cannot detect emotion, fine changes in the mood, refined or not so refined jokes. The translators are demotivated and the films are badly translated as a result.

And if there is still a question hovering: “Should we be worried?”, then let me give you a few figures.

According to statistics, for over 2 decades now the UK reads only 1.5% translated literature, compared to 19.5% in Italy, over 16% in France and 13% in Germany.

The problems with translating works in English are the following:

- As English is such an international “lingua franca” – forgive my Latin! – too many writers, including foreign-born and bred, prefer to write in English

- Editors and publishers in UK rarely speak any other languages than English any more! When they go to book fairs around the world, they choose books already written in English. They are choosing the easy – and the more rentable – option

- It all starts from school, according to Ann Morgan, who is reading 196 books – one from every country in the world – for her blog A Year of Reading Around the World. Morgan says that “at school in the UK we don’t really read translations, we just don’t develop that habit”; unlike French or German students, schoolchildren below A-level in the UK – with the exception of International Baccalaureate students – are only asked to read literature originally written in English

It is true that since 2016 the Mann International Booker Prize have decided to give half of its award to the translator. It hasn’t been long enough though for translators to feel like artists.

So translation as a function of bringing languages and cultures together has been undermined for a long time, especially in the Anglo-Saxon world. And yet translations are known to have saved nations. I don’t just think of the first “vulgar” translations of the Bible or the translations that brought to us the ancient knowledge of mathematics, medicine, astronomy and history.

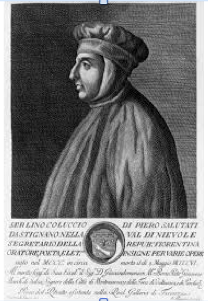

At the end of the 14th-start of the 15th century The Florentine Republic survived 12 years of siege from the powerful Visconti to whose sword fell all Italian city-states: Pavia, Siena, Milan, Bologna… The leader of Florence, Coluccio Salutati, who sent ambassadors around the world called Oratore – speakers – managed to develop in his people the virtue of willpower, making them realise that they were the real descendants from the Roman and Greek republics. How? After years of agreeably declining to translate into Tuscan the “pagan” Roman authors, Coluccio Salutati decided to defy the Church and bring into the city the works of Virgil, Ovid, Plautus, Seneca, Socrates, Homer, translated them from Latin and built self-esteem amongst all Florentines who managed to defeat the Visconti. Virgil and Ovid, Homer and Herodotus talked about heroes and Gods. Their stories gave motivation to the Florentines to withstand the siege and to start producing some of the greatest art known to man, in turn translating Latin and Greek verse into sculptures, frescos and paintings.

Thus started the European Renaissance.

Of course, this is an over-simplified version of events.

But since King James’ Bible, I dare you to find in your recent memory such an important translation that has changed the course of our lives.

English developed historically form German, Latin, Danish, French etc, including words like “chutney”, “bungalow”, “punch”, coming from Hindi, and many more from other colonial sources. Can we mechanically transfer whole proverbs, created by the wisdom of other nations, over many centuries, into the English language? Can we transfer English proverbs as easily into other languages? In the earlier example with “Oops a daisy”, it was obvious that Google Translate is not ready yet for that.

There are however multiple indications that Google would be moving into sophisticated, complex concepts like grammar, the way robots have been promising to imitate humans. The computers are learning from us. As the proverbial Sophia the robot shows us in many video clips on youtube, robots are learning from us.

She learns automatically, superficially. However, in order to start creating, not replicating language, Sophia needs to be implanted into a society of humans or robots. Is that possible in the future? A mere linguist like me cannot answer that question.

There is a question from me: Will the Eliza effect blind us with science? The Eliza effect, from an old 1990s scientific experiment, represents our overwhelming feeling that robots are more perfect than humans therefore more believable. Is Google translate more believable – and convenient – than our own curiosity to learn?

Translation is part of every interaction we undertake. We don’t translate only from language or only into language. We translate gestures, looks, pallour of the loved one’s face, pitch or aggressiveness of the voice, pictures, music. Translation of certain signs save our lives, warn us or draw us nearer to others with joy. How many times have you heard the word “can you translate this for me, please”? How about the word “interpretation” which in linguistics means “oral translation”, and has its uses in most arts, including music.

“Soon we must all face a choice between what is right and what is easy.” – says Dumbledore to Harry before the big battle for Hogwarts begins.

Soon we will have to fight a battle for the survival not of some languages, but of language as a human function.

Just think of the power of the emoji.

Google is easy. Google is a shortcut. A life saver, but not a translating tool.

So what do I suggest?

I am not going to use the highly emotional, commanding Imperative mood, nor would I use exclamation marks that may upset people. How about a questioning Conditional?

Here it goes:

1) Holiday makers, prior to a trip to Russia, for example:

- Wouldn’t you rather read a few travel websites for specific expressions coming from Russian nationals? There are many of those on the Internet, on Lonely Planet and Trip Savvy. The advice comes with cultural connotations.

- If you know in advance of your trip, how about catching up on some history and some good translation from Russian of Gogol’s Dead Souls or Chekhov’s plays?

- If you have a deeper interest in, say, art or literature, why not find on Amazon for small pennies guides and topic-oriented phrase books that may lead you to discovering more about Russian cuisine than just ordering pelmeni?

- Spend longer time over a piece of text, whether it is in English or any other language you can use. Make it yours, analyse it, search the words and expressions that make your mind trip over.

- Read translated literature. Even if you are reading in English, the foreign culture you’ll have to assimilate while reading apparently makes the grey cells work harder and avoid Dementia.

2) Wouldn’t you read a translated classic rather than a bad novel in vernacular?

3) Please install Google Translate for all language emergencies, quick solutions and the odd gap to fill by a matching word. And check what you are writing or saying.

I leave for the end a beautiful quote by Albert Camus, my favourite writer. It is not his quote that I would like you to focus as much on, it is the masterful translation, in comparison to the Google version.

Elen Conroy Kennedy (translator):

“In the depth of winter, I finally learned that within me there lay an invincible summer.”

T