Ralyo was born on November 1st, All Souls’ Day, 1906 in the village of Great Clover, Bulgarian Thrace. He was born just a year after his refugee family settled in Bulgaria. They had run away from Aegean Thrace, their home and their land eaten up by yet another Balkan War, their roots cut off to stay and disintegrate somewhere in modern northern Greece. Yet they felt that they belonged, with their language and with their blood, in this Thracian valley that spread into a foreign land.

Ralyo’s father and grandfather were millers. Thrace was – and still is – the fertile breadbasket of South-Eastern Europe, land of wine, tomatoes and barns regurgitating with wheat and fruit. Birthplace of myths, music and Orpheus. A miller would be milling golden grain into flour for years to come in such a Paradise.

But what would the life of a refugee miller be? Arriving in Bulgarian golden Thrace, refugees aplenty. Ralyo’s family settled near an already existing village called Clover. The refugee village however was so much bigger that, since there was yet no name for it, the suspicious neighbours from Clover named it Great Clover. (Now both villages have been submerged these seventy years under the waters of a dam, where the Communists built an almighty electricity power plant feeding Bulgaria and parts of Turkey.)

Suspicious and unwelcoming a lot of the neighbours indeed were. Who needs another miller in the neighbourhood?

Ralyo needed to find his feet away from the mill. He was accepted to study at university. At night he’d stoke the steam engines at the train station, at day he’d study as if his life depended on it. And his life depended on it indeed. When Ralyo, the eldest son of the miller, was twenty-one, he already had seven younger siblings and was the principal teacher of the communal school in Great Clover.

One day some parents stormed into his classroom to ask him to run home because the mill and his home were on fire. Real fire, started by the hands of intangible suspicion, fear and jealousy. Arriving at his burning home, the handsome, tall, blue-green-golden eyed Ralyo saw his distraught mother screaming as the flames engulfed the small adobe house and the greatest treasure inside it: Ralyo’s eight-month old sister Turna. Ralyo dropped everything and ran into the house.

“Don’t go, Rali, I don’t want to lose you, my son! Whatever God has in stall for your sister, let it be! Leave it to Him to save her!”

Ralyo had gone in for a long time. Or so it seemed to his mother and siblings. Eventually he emerged out with the screaming baby and got drenched in pales of water, just as the fire fighters were arriving from their station in the nearby town.

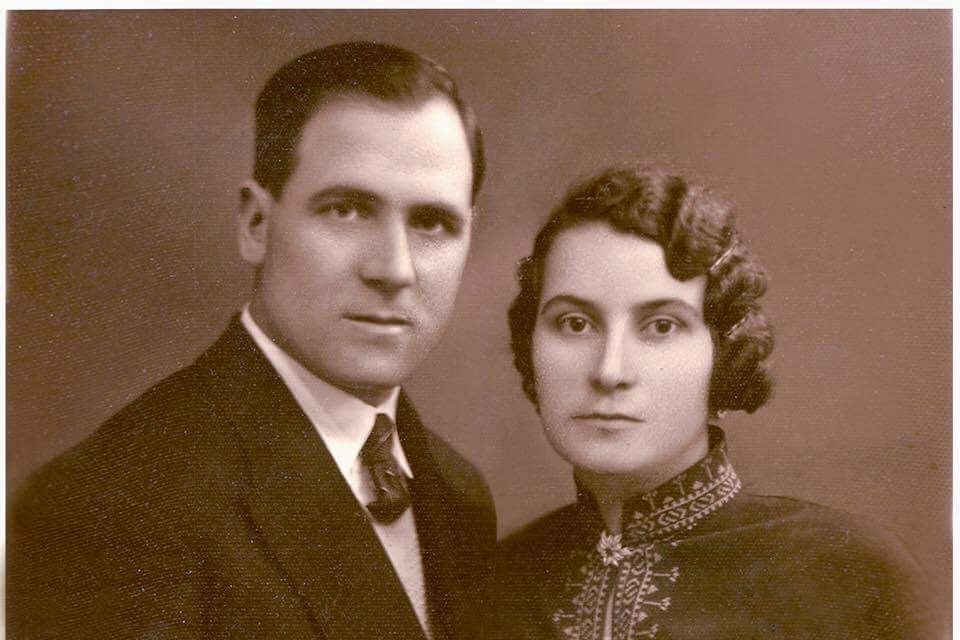

Turna had bright blue eyes like forget-me-nots. Big blue eyes that later she gave to her own sons. But before she grew up and married, she lived, during the war and beyond, under the roof of her brother’s young family: Ralyo, strong and serious, was already a respected history and literature teacher, happily mismatched with his sweet bourgeois wife and their daughter.

Aunt Turna was closer in age to the young child of the couple than to her own brother, so they grew up for a while like sisters. Turna became a teacher like her brother. She venerated everything about that blue-green-golden eyed Ralyo who, despite the heartbreak of two first stillborn sons, believed and fought for the life that grows on and thanks to the Thracian soil.

Ralyo’s one and only daughter – and Turna’s friend – became a doctor. Ralyo’s daughter was initially refused university entry and forced to work for two years by the Communist regime because she came from a “bourgeois family”, on her mother’s side. Teaching accordion in the still muddy villages of 1950s Bulgaria, she developed a nasty blood disease called “blood tuberculosis” that nearly killed her in her first year of Medical Academy. Later, aged thirty-two, having already had two children, she would prepare a thesis on psychiatric handicap within the new labour law, only to be refused to validate it because she was not a Communist.

No one in that family was a member of the Communist Party in a country where 95% were members. Ralyo was a member of the Agrarian union, a ghostly organisation that, he hoped, was shielding landowners’ pride but in fact was a sidekick to the Communist party.

He was decorated many times by the government for his contribution to education – he had many medals that sometimes he’d take out in the dead of night to clean with vinegar. He didn’t want to make them part of his “day self”. But his two grand children who never went to sleep when they were told, especially when on holiday, were watching him. He was proud. They were proud.

One winter evening, after coming into the garden from games in the snow with her friends, through the cold February-frosted window Ralyo’s six-year old granddaughter saw a picture that curdled her blood even if she could not understand it. Her tall, handsome grandfather (who also knew very well how to insult his enemies under his nose) was sitting small at the table, towered over by two men in furry hats in the kitchen. He had his stubborn face on, but she could read fear on it. Later she would find out that yet again the Communist party officials had been to the house to convince him to become member of their party. They knew what an asset he would be. To this day she doesn’t know what explanations he used to rebuff them. But somehow the authorities chose not to bother him the way they tragically “bothered” others, such as his friend who, one night in the late 1940s had disappeared, never to return home. Others disappeared too, friends or not. The young child became cross and angry at her granddad when she saw him small. She refused to accept that he should look small. Little did she know that his act was anything but small.

Ralyo’s grandchildren helped him with gusto when he polished and cleaned his big numismatic collection of ancient Byzantine and Roman coins that he, aged around seventy and his grandson, aged around nine, gathered when they worked hard in the summers with the archeological excavations at the burial mounds in the neighbouring Thracian fields. At his death he bequeathed his collection to the Museum of his town Nova Zagora where it still lives.

Ralyo used to say that the land of Thrace is full of the greatest beauty life can offer. He adored the folk music and dances (horo and ruchenitsa) of Thrace and the Rodope, he knew their myths and legends and their history. He worked fervently Thrace’s fertile land. That is why he resented his wife’s religious piety. Anticommunist, yes, but also anti-religion, he believed in two things: culture and the land. He would wake up at 3.30am to tend to the garden: the orchard, the vegetables, the vine and the flowers, to talk to them, to prepare them for the day. Then he would wash, have a piece of bread for breakfast and go to school to teach. He knew the greatest Bulgarian poems by heart. He spoke French. His memory for dates and events was phenomenal. He was severe and strict and could not suffer fools gladly. His own daughter, former pupil, remembered people being afraid of him. And venerating him. Seeing their Granddad, albeit already retired, leaving the house in his long impeccable raincoat, tie and suit, felt hat, tall and handsome even at 70, his grandchildren thought that he was invincible and that he knew everything. Everywhere the children went round town, people pointed at them with deference saying “These are Mr Bonev’s grandchildren.”

Turna became a Communist, like so many others, because she did not have her brother’s strength and his stubborn face, and because she wanted the best for her children.

When Ralyo suffered his first heart attack and came to stay with his doctor daughter and his grandchildren for a few days during the medical investigations, the children did not believe his illness. Just like that night, standing at the kitchen window, cross with him for his “littleness”, the eleven-year old girl begrudged him this weakness – that they still did not know was a heart attack. She could not accept that this eternal rock of the family who once ran after the train because she had forgotten her hat and gloves, who adored her, she could not accept that he could be vulnerable.

Few imagined him vulnerable. To this day she sees his blue-green-golden eyes filled with pain fixed on her eleven-year old brown eyes as if imploring for a hug. She remembers him, leaving the flat on a stretcher to go to the hospital, saying

“You all will eat and drink at my funeral.” This is when she saw him for the last time.

Maybe somehow he foresaw his dark fate. A fate that still grips his family with guilt. He would be accepted into the ward of one of his former students, who, despite being one of the fools Ralyo could not suffer gladly, had become a cardiologist and a Communist. He banned all of Ralyo’s family from visiting him, under the pretext of keeping him safe. The ban extended to his own daughter who worked at the same hospital. Why? Did he know that this would kill him? The eleven-year old girl could see her mother’s white face, the dark circles under her eyes, every night. Her mother did not cry, could not cry. Already a respected psychiatrist, in charge of the whole of Southern Bulgaria, in her love for her father she was helpless, crucified by the cruelty of spineless ideology. And possibly – vengeance.

The only person admitted to see Ralyo was Communist Turna. At the time she would not dare to report back how heartbroken their Granddad was that not one of the family would pay him a visit. But the family suspected his grief. At home nerves were pulled to a breaking point.

One night – or very early morning – I was woken up by a quiet shuffling around my bed. My ten-year old brother had gathered the sheets of his bed and tied them in a rope not too dissimilar to those from the romantic swashbuckling French films of the 1950s that the Communist authorities fed us in the summer open-air cinemas. He told me that he was going to the hospital to climb to the ward and “save Granddad”. I almost agreed to follow, only realising at the last moment that we did not know where and how exactly to find his ward in the big multi-storey building.

My Granddad passed away after a second heart attack completely alone, catheters coming from everywhere of this proud, handsome, invincible body.

The only person allowed to see the body and collect it was my Great-Aunt Turna. She came to tell us, choosing not to use the phone, by foot, that he had died. Did she tell us or did we see it on her face, unable to finish a sentence through her tears? Her guilt was that she could not return the favour and save him. But she had named one of her sons after that eldest brother who had saved her as a baby, who had given her home and education. Her other son bears the name of St Cyril – one of the brothers Cyril and Methodius who created the Cyrillic alphabet. The patron Saint of Ralyo and Turna in their vocation: teaching.

My Great-Aunt Turna died yesterday. She was buried today. I expected it. She was ninety-one, ill from about two-three weeks ago, unsteady for a few years now. I went to see her every summer. She has met many times with my sons, one of whom looks remarkably like my Granddad.

My whole existence is exhausted from losing another source of truth about my real childhood. My early life, marked by flickers of memory rather than reality, resembles the Thracian myths and folk tales, not true history. I knew I had also lost, when missing my “Goodbye” to Aunt Turna, the chance to hug her and hope that, when she meets up with Granddad up there, she’d ask him to forgive his granddaughter.

Now they are both quiet. Looking at me with their bright, loving eyes. Tall, handsome and cultured, blue-green-golden where the blue is like forget-me-not.

@doracourt/19May2019